Quantum simulation (Supremacy)

Quantum simulation with digital quantum computer (IBM)

Protocol

First of all, it is important to notice that IBM did not claim quantum supremacy in this experiment (we classify it as a supremacy experiment due to its closeness to the experiment done by D-Wave company). It also helps introduce challenging methods commonly used to refute supremacy claims.

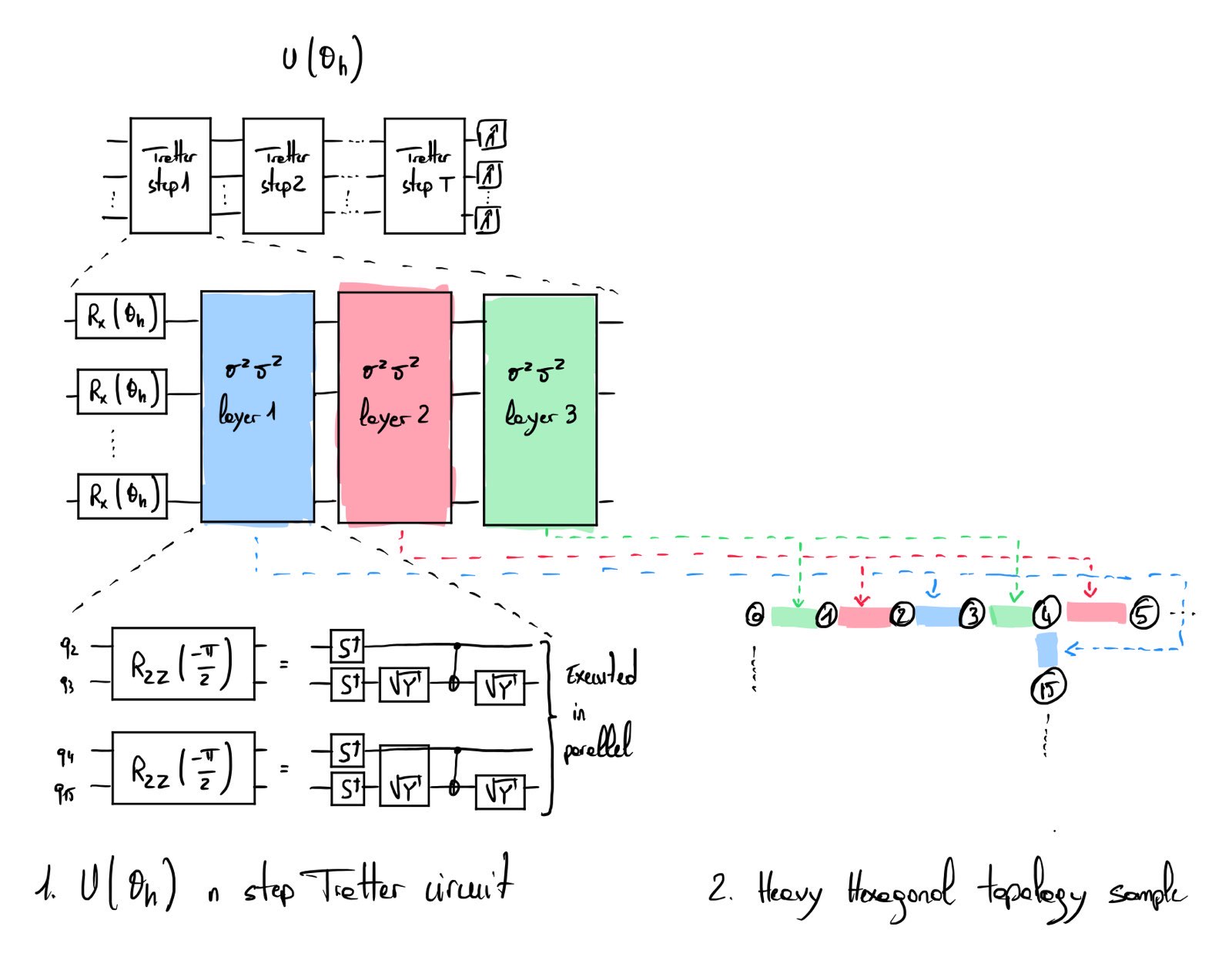

In [1], Y. Kim et al. assess the potential of IBM quantum computers at solving quantum simulation problems with a digital implementation of a continuous-time Hamiltonian evolution. Let the IBM hardware graph (heavy hexagonal topology) be defined as a set of vertices and edges \(G = (V, E)\). The Hamiltonian of interest is determined by the heavy hexagonal topology:

\[H = -J \sum_{(i, j) \in E} \sigma_i^z\sigma_j^z + h \sum_{i \in V} \sigma_i^x\]The experiment aims to sample the output distribution of the trotterized evolution of the above Hamiltonian. The weight \(J\) is judiciously chosen so that each \(\sigma^z\sigma^z\) can be implemented with only a single CNOT gate (hence minimizing the noise induced by these gates). The weight \(h\) is related to the parameter \(\theta_h\), which parameterizes the rotation-x gates of the quantum circuit. For a fixed number of Trotter step \(T\), a corresponding circuit is built, and the average value of pre-defined observables is measured with different values for the \(\theta_h\) parameter. As the circuit is built over the heavy hexagonal topology (a graph with maximum degree 3), a single trotter step can be done with 3 CNOT depths (see Fig. 1 and 2).

The observables are defined as weight-x observable, where the x corresponds to the number of qubits involved in the observable. For example, a weight-4 observable defined as (\(X_{1, 2}Y_{4}Z_{3}\)) denote that qubits 1 and 2 are measured in X basis, qubit 4 in Y basis and qubit 3 in Z basis. The experiment uses the Zero-Noise Extrapolation (ZNE) method to mitigate the quantum noise.

The first benchmark consists of evaluating the behavior of quantum circuits on verifiable instances (using only Clifford circuits by setting \(\theta_h = \frac{\pi}{2})\). The second benchmark involves non-clifford circuits but choosing observables that are exactly verifiable classically. The third experiment uses non-clifford circuits beyond the verifiable regime, with weight-17 observables and 5 Trotter steps in the first case and single qubit magnetization with 20 Trotter steps in the second case.

The performance comparison is done with Matrix Product State (MPS) methods and Isometric Tensor network states, which appear to have large prohibitive costs for large instances. For the third experiment, results were obtained with the quantum computer in 8h for each individual data point \(\theta_h\) for the specified weight-17 observable. The weight-1 average magnetization was measured in 4h for each individual data point \(\theta_h\). The authors mention that the global processing time could be reduced to 5 minutes (by drastically reducing the classical processing time).

Challenges and refutations

The following table summarize the challenges and refutations done concerning this experiment.

| Date & Ref | Challenge type | Instance | Method | Classical hardware | emulation time | Better accuracy ? | Data or source code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023 [2] | Refutation | Weight-17 observables Weight-1 magnetization |

Belief propagation tensor network | Single CPU Core | Yes | [3], [4] | |

| 2023 [5] | Spoofing | Weight-17 observables Weight-1 magnetization |

Emulate smaller instances (30 qubits) | Single GPU | < 1 sec / point | [6], [6] | |

| 2023 [7] | Refutation | Weight-17 observables Weight-1 magnetization |

Sparse Pauli dynamics | Single CPU Core | 1-2 mins / point | ||

| 2024 [8] | Refutation | Weight-17 observables Weight-1 magnetization |

Sparse Pauli Dynamics (SPD) PEPS PEPO Mix PEPS, PEPO |

Single CPU Core | 10s for SPD | Yes | [9], [10], [11] |

| 2023 [12] | Refutation | Weight-17 observables Weight-1 magnetization |

PEPO | Single CPU Core | < 3 sec / point for weight-17 | [13] |

Quantum simulation with quantum annealing (D-Wave)

Protocol

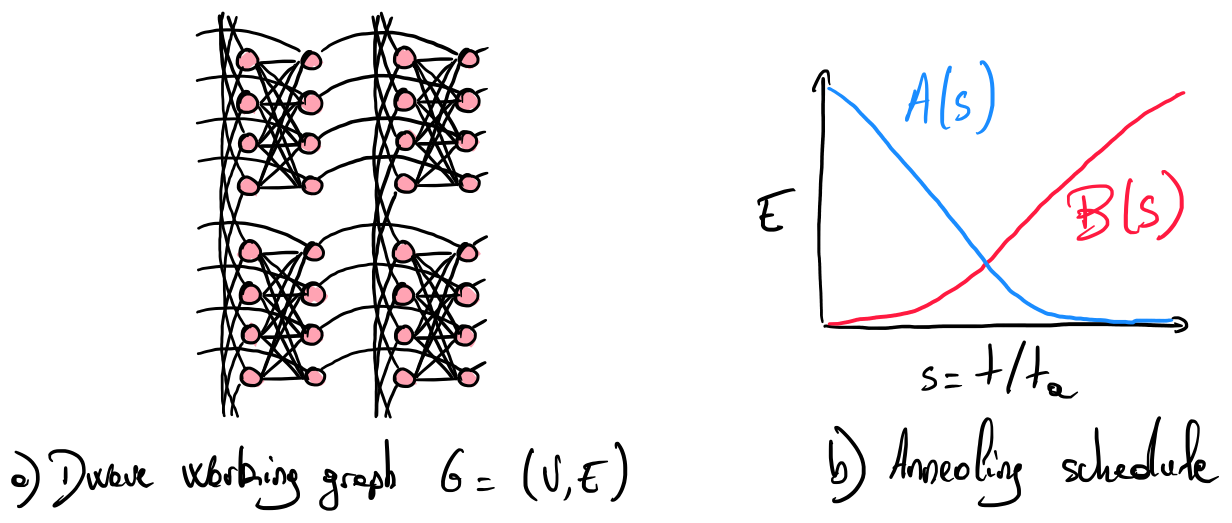

In [14], A. D. King et al. establish a protocol to assess the computational supremacy of D-Wave systems. These systems are analog-based quantum computers (a paradigm slightly different from gate-based quantum computers). An example of the qubit layout is shown in Fig. 3. where each qubit is represented by a node and each programmable coupler by an edge.

The evolution of such systems can be described with a Hamiltonian operator linearly interpolating two Hamiltonians: an initial Hamiltonian \(H_\mathrm{I}\) dominating the evolution at the beginning (\(A(0) \gg B(0)\)) and a final Hamiltonian \(H_\mathrm{F}\) dominating the end of the evolution \(H_\mathrm{F}\) (\(B(1) \gg A(1)\)). The strength of each Hamiltonian is driven by the annealing schedule (see Fig. 4). The annealing fraction \(s = t/t_\mathrm{a}\) is expressed according to the current time \(t\) and total annealing time \(t_\mathrm{a}\):

\[H(t) = A(s) H_{I} + B(s) H_{F}\] \[H_{I} = - \sum_{i \in V} \sigma_i^x\] \[H_{F} = \sum_{(i, j) \in E} J_{i,j} \sigma_i^z \sigma_j^z\]The supremacy experiment’s annealing time is really short: \(t_a \in \{7, 20\}\)ns. The experiment aims to show that sampling the quantum computer’s output distribution is hard to reproduce classically. The principal figure of merit used in this experiment is the correlation error \(\epsilon_c\) defined as:

\[\epsilon_c = \left( \frac{\sum_{(i,j) \in E} (c_{i,j} - \widetilde{c}_{i,j})^2}{\sum_{(i,j) \in E}\widetilde{c}_{i,j}^2} \right)^{1/2}\]where \(c_{i,j} = \braket{\sigma_i^z \sigma_j^z}\) denotes the two-point correlation function computed for the \(n(n-1)\) couples of qubits (i.e., local and non local correlations).

For small instances (\(n \leq 64\)), the results generated by the quantum computer are verified and validated with ideal classical simulations (using the MPS method). Beyond this regime, the output of the quantum computer is checked to comply with the theoretical results of quantum mechanics (i.e., by estimating the Binder cumulant and showing that its value decreases with a power law of the Kibble-Zurek exponent). Each instance is run with low precision coupling weights \(J_{i,j} \in \{-1, 1\}\) and high precision coupling weights \(J_{i,j} \in \{-\frac{128}{128}, -\frac{127}{128}, ..., 0, ..., \frac{127}{128}, \frac{128}{128}\}\).

The classical methods used for comparison are:

- MPS

- Projected Entangled-pair States (PEPS)

- Neural Quantum States (NQS)

The list of instances evaluated is presented in the following table:

| Date & Ref | Category | Dimers ? | \(L_x \times L_y \times L_z\) | qubits | Graph particularity | Classically verifiable | QPU | annealing time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2025 [14] | Square latticeCylinder | no | \(8 \times 8\) | 64 | 4-regular graph | yes | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns |

| 2025 [14] | Square latticeCylinder | no | \(18 \times 18\) | 324 | 4-regular graph | no | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns |

| 2025 [14] | Cubic dimer | yes | \(3 \times 3 \times 3\) | 18 | yes | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns | |

| 2025 [14] | Cubic no dimer | no | \(3 \times 3 \times 3\) | 18 | yes | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns | |

| 2025 [14] | Cubic dimer | yes | \(6 \times 6 \times 6\) | 424 | no | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns | |

| 2025 [14] | Cubic no dimer | no | \(6 \times 6 \times 6\) | 424 | no | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns | |

| 2025 [14] | Diamond | no | \(4 \times 4 \times 8\) | 32 | 4-regular graph | yes | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns |

| 2025 [14] | Diamond | no | \(12 \times 12 \times 16\) | 576(9 defects) | 4-regular graph | no | Adv2 | \({7, 20}\)ns |

| 2025 [15] | Cubic dimer | yes | \(12 \times 12 \times 12\) | 3367 | no | New Adv2 | \({7, 20, 40}\)ns |

Concerning the study of the runtime of classical computers, A. D. King et al. evaluate the time and comptutational space required by MPS method to match their results. They conclude that such method would take millions of years using Frontier supercomputer. They do not extensively benchmark the PEPS method using the argument that this method does not reach a sufficiently suitable correlation threshold with a descent scaling.

2.1 Belief propagation tensor network method (Challenge 1)

In [16], J. Tindall et al. challenge the claim by using a tensor network method to approximate the value of the two-point correlation function. They reproduce verifiable instances for cylindrical, diamond cubic, and dimerized cubic instances (up to 50 spins) for annealing times \(t_a \in \{7, 20\}\) ns. Their tensor network method exhibits a better correlation error than PEPS and QA results presented in the initial paper [14]. The authors suggest that this tensor network method scales linearly with the problem size. With 50 spins, their method can sample a single two-point correlator in 15s using a single Intel Skylake.

For instances beyond the verifiable regime, they estimate the Kibble-Zurek exponent with a different method than the one used in [14] that requires less computation (instead of directly using the Binder cumulant that requires the investigation of 4-point correlation). With this method, they demonstrate good agreement with the theory for cylinder lattices up to size \(18 \times 18\).

This method is considered a challenge as they do not completely reproduce the experimental results provided in [14]. However, the sampling time is impressive as they are able to generate a single spin-spin correlation factor in \(15.5\)s using a single CPU.

2.2 Time-dependent Variational Monte Carlo (Challenge 2)

In [17] L. Mauron and G. Carleo introduce a new classical Monte Carlo-based method able to approximate the ideal quantum evolution up to 128 spins for the 3-D diamond lattice in a few days with only 4 GPUs. They use a fourth-order Jastrow-Feenberg ansatz to approximate the wave function defining the quantum evolution. Using this operator, they are able to obtain approximately the same correlation errors as those generated by the quantum annealer in [14]. This comparison is done for systems up to 128 qubits with an annealing time of \(7\)ns.

Based on their method, they attempt to extrapolate their results, estimating that the largest instances could be solved classically using the Frontier supercomputer for a few hours.

This publication is also considered a challenge as they do not completely reproduce the experimental results provided in [14]. The experiment is done using the shortest annealing time (\(7\)ns), which is expected to be the simplest case to simulate with limited correlations between the spins sites (for example, it is shown in [14] that the PEPS performance decrease for slower quenches). However, their classical method seems to be very competitive with a nice performance scaling, suggesting that further experiments could weakly refute the initial claim done by D-Wave company.

The D-Wave research team has made a constructive comment on both challenges [15].

3. References

- [1]Y. Kim et al., “Evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance,” Nature, vol. 618, no. 7965, pp. 500–505, 2023.

- [2]J. Tindall, M. Fishman, E. M. Stoudenmire, and D. Sels, “Efficient tensor network simulation of ibm’s eagle kicked ising experiment,” Prx quantum, vol. 5, no. 1, p. 010308, 2024.

- [3]J. Tindall, M. Fishman, E. M. Stoudenmire, and D. Sels, “Belief Propagation - Tensor Network State - IBM Heavy Hexagonal Data.” 2023 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/JoeyT1994/BP-TNS-Data/tree/main/IBMHeavyHexData. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [4]“ITensorNetworks.jl.” 2022 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/ITensor/ITensorNetworks.jl. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [5]K. Kechedzhi et al., “Effective quantum volume, fidelity and computational cost of noisy quantum processing experiments,” Future Generation Computer Systems, vol. 153, pp. 431–441, 2024.

- [6]K. Kechedzhi et al., “Cirq source code 1 Quantum utility.” 2023 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/quantumlib/Cirq/blob/main/examples/advanced/quantum_utility_sim_4a.ipynb. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [7]T. Begušić and G. K. Chan, “Fast classical simulation of evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2306.16372, 2023.

- [8]T. Begušić, J. Gray, and G. K.-L. Chan, “Fast and converged classical simulations of evidence for the utility of quantum computing before fault tolerance,” Science Advances, vol. 10, no. 3, p. eadk4321, 2024.

- [9]K. Kechedzhi et al., “Carxiv-2308.05077-data.” 2024 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/tbegusic/arxiv-2308.05077-data. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [10]K. Kechedzhi et al., “Mixed picture tensor network, lazy belief propagation based quantum dynamics.” 2024 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/jcmgray/mixpic-bp-quantum-dynamics. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [11]K. Kechedzhi et al., “Sparse Pauli Dynamics.” 2024 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/tbegusic/spd. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [12]H.-J. Liao, K. Wang, Z.-S. Zhou, P. Zhang, and T. Xiang, “Simulation of IBM’s kicked Ising experiment with projected entangled pair operator,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2308.03082, 2023.

- [13]H.-J. Liao, K. Wang, Z.-S. Zhou, P. Zhang, and T. Xiang, “Simulation of IBM’s kicked Ising experiment with Projected Entangled Pair Operator.” 2023 [Online]. Available at: https://github.com/navyTensor/PEPO. [Accessed: 07-Apr-2025]

- [14]A. D. King et al., “Computational supremacy in quantum simulation,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.00910, 2024.

- [15]A. D. King et al., “Comment on:" Dynamics of disordered quantum systems with two-and three-dimensional tensor networks’ arXiv: 2503.05693,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.06283, 2025.

- [16]J. Tindall, A. Mello, M. Fishman, M. Stoudenmire, and D. Sels, “Dynamics of disordered quantum systems with two-and three-dimensional tensor networks,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.05693, 2025.

- [17]L. Mauron and G. Carleo, “Challenging the Quantum Advantage Frontier with Large-Scale Classical Simulations of Annealing Dynamics,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.08247, 2025.