Many-body Quantum Score (MBQS)

Motivation

Quantum many-body problems are believed to be particularly adapted to quantum computers and may provide a setting in which quantum advantage can be realized. The MBQS protocol aims to benchmark quantum computers’ ability to reliably simulate quenched Hamiltonian dynamics. This protocol is scalable and is designed for analog and gate-based quantum computers.

Protocol

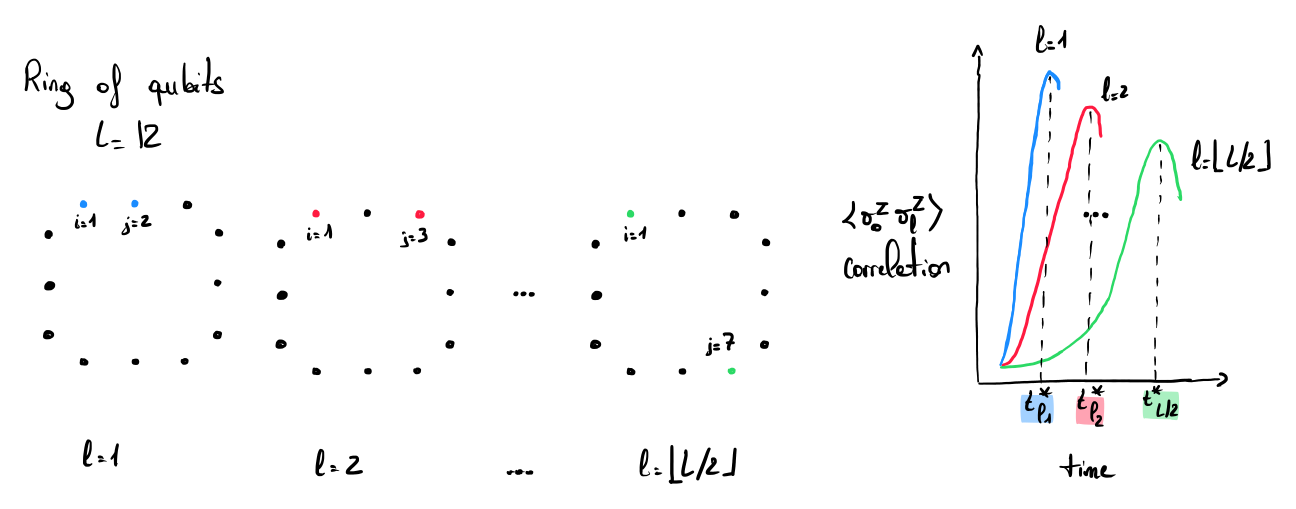

The MBQS protocol was proposed in 2026 by H. Erbin et al. [1] and evaluates the ability of a quantum computer to simulate the Hamiltonian dynamics of a 1D Ising chain or ring. The main idea is to evaluate the correlations between different qubits (sites) constituting the chain at a specific time \(t^*\). The time \(t^*\) is theoretically and efficiently derived for 1D systems and corresponds to a correlation peak depending on the distance between the two sites being evaluated. In the picture, three correlation peaks are display, one that corresponds to the length \(l=1\) (blue), one that corresponds to the length \(l=2\) (red) and one that corresponds to the length \(l=6\) (green). The value \(t^*\) increases with the distance between the qubits. As the distance increases, the magnitude of the peak decreases (see diagram in the picture). The correlation values obtained for each length \(l\) are then compared to the ideal values derived theoretically for the Ising model in polynomial time \(O(L^3)\) (for rings composed of \(L\) qubits, the maximum length \(l\) corresponds to \(\lfloor L/2 \rfloor\)). In this way, the protocol is able to check the correlation spread among the device and use this quantity as a proxy for measuring the entanglement rate of the system.

Steps of the protocol:

- The system is prepared in an initial state (\(\ket{00...0}\) in the paper).

- The system is evolved until \(t^*\) with the Ising model Hamiltonian.

- The qubits are measured, and the correlation between qubits \(i\) and \(j\) is computed.

- The experiment is repeated several times for different lengths \(l\) (and hence different \(t^*\)).

The 2-point correlation between qubits \(i\) and \(j\) is evaluated with the formula: \(g_l(t) = \left< \sigma_i^z(t) \sigma_j^z(t) \right> - \left< \sigma_i^z(t) \right> \left< \sigma_j^z(t) \right>\)

where \(\left< \sigma_i^z \right>\) corresponds to the average eigenvalue associated with the observable \(\sigma^z\) on the qubit \(i\). For each length \(l\), the value of the 2-point correlation function is computed experimentally with the quantum computer \(g_l^{\mathrm{exp}}(t)\) and theoretically calculated with a classical computer \(g_l^{\mathrm{th}}(t)\). The comparison between these two values gives a scoring function \(P_2(L)\) (see eq. 2.4 of [1]) that equals \(1\) for classical random output and \(0\) for a perfect result. The quantum computer is assumed to validate a score \(L\) if \(P_2(L)\) gets below a certain threshold. The authors propose a notation for the MBQS protocol: \(MBQS_{\mathrm{+}}(0.05)\), where the \(+\) denotes the initial state \(\ket{+}\) and \(0.05\) the value of the threshold.

This protocol can be extended to gate-based quantum computers using Trotter approximation or block-encoding methods. The initial paper example focuses on qubits arranged in a ring structure. This protocol might also be extended to open boundary conditions with chains of qubits.

Assumptions

- The compiler may use all the possible tricks to improve the mapping of the quantum circuit, which can lead to high extra-processing time.

- Error mitigation is authorized in this protocol. However, the authors recommend reporting values with and without error mitigation methods to capture the raw performance of the quantum computer.

Limitations

- This protocol is limited to 1D geometry. The exact derivation for more complex geometries.

- As the time \(t^*\) scales with \(L\), the height of the peak deacreases exponentially. It entails an exponential number of measurements required to precisely evaluate the 2-point correlation function (see fig. 26 in the article [1]).

Results

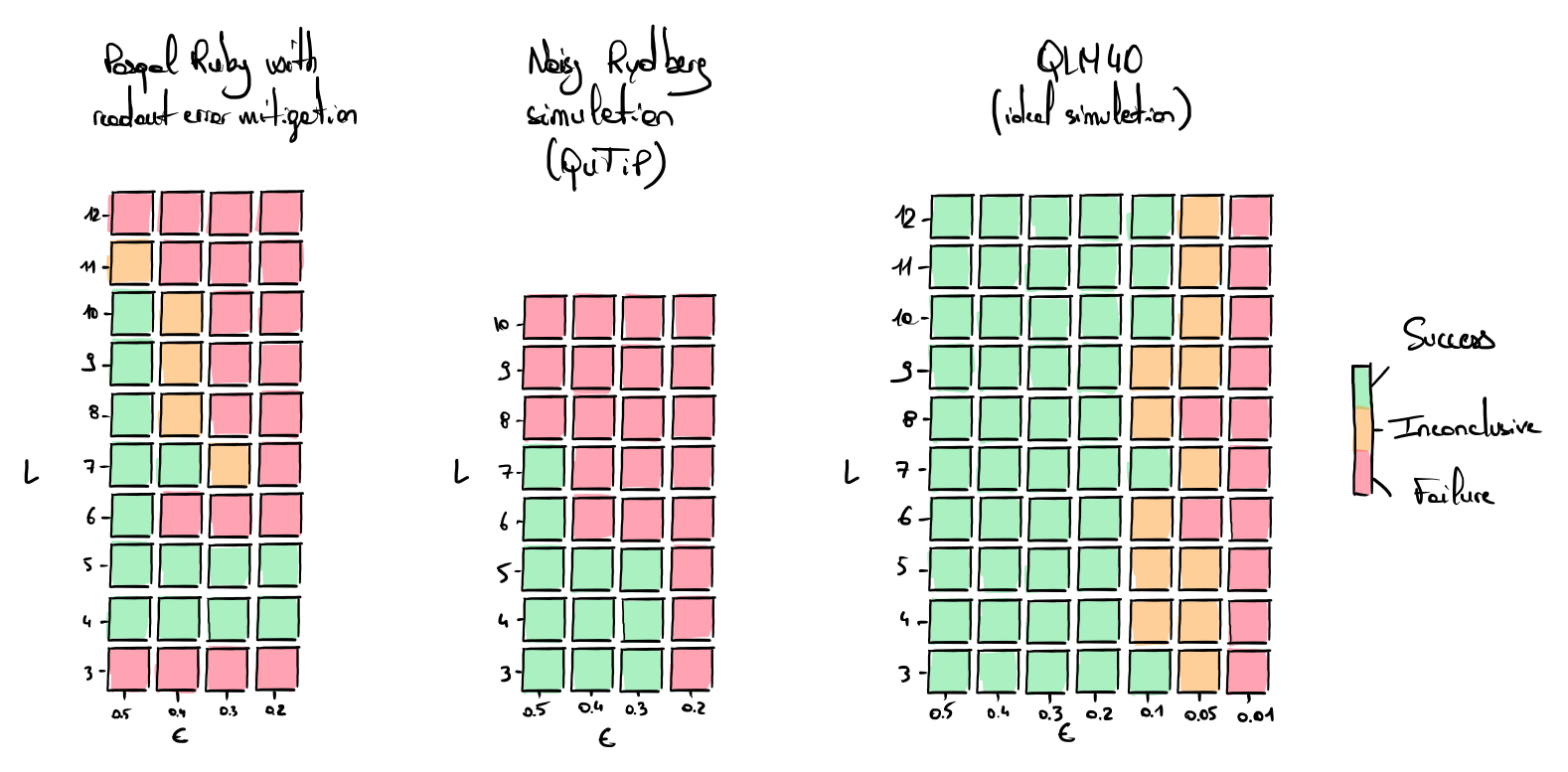

The following figure is reproduced from the article [1] and plots a volumetric representation of the final score for different threshold values \(\epsilon\) and different lengths \(L\). The evaluation is conducted on a Pasqal device with error mitigation (left), a noisy emulator (middle) and an ideal noiseless emulator (right). The ideal emulation shows that any length \(L\) from 3 to 12 can be validated with a threshold \(\epsilon = 0.2\) (right plot). The noise of Pasqal device makes the threshold \(\epsilon = 0.2\) inaccessible beyond \(L=5\). The readout error mitigation method improves the results produced by the Pasqal machine compared to a noisy emulations without error mitigation.

Implementations

There is currently no publicly available implementation of the MBQS protocol.

References

- [1]H. Erbin, P.-L. Burdeau, C. Bertrand, T. Ayral, and G. Misguich, “Many-body Quantum Score: a scalable benchmark for digital and analog quantum processors and first test on a commercial neutral atom device,” 2026. Available at: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:284532739