Multi-qubit Clifford Randomized Benchmarking (CRB)

Motivations

The primary motivation behind developing multi-qubit Clifford Randomized Benchmarking (also called Standard Clifford Randomized Benchmarking) was to generalize the single-qubit randomized benchmarking protocol to systems comprising multiple qubits. This extended protocol was introduced in 2010 by E. Magesan et al. [1].

Protocol

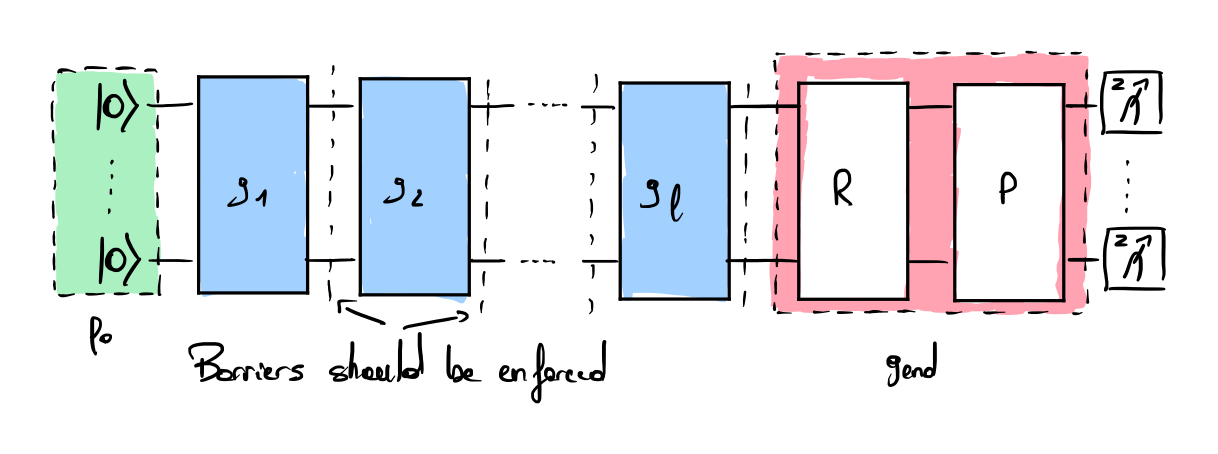

The protocol utilizes the multi-qubit Clifford group \(C_n\) to benchmark a quantum system with \(n\) qubits. For each sequence length \(l\), Clifford gates are uniformly and efficiently sampled from \(C_n\) [2]. Each gate of the Clifford group is efficiently decomposed into a sequence of single and two-qubit gates, with depth scaling as \(O(n^2 / \log(n))\) [3]. The inverse unitary \(R\) is efficiently computed from the sequence \(g_lg_{l-1}...g_1\) [4], and a final unitary \(P\) is randomly and uniformly chosen to produce an eigenstate of the observable \(\sigma^z\) (The unitary \(P\) was not used in the initial protocol, but is considered to be a best practice). The success metric is the probability of observing the Identity up to the random Pauli gate \(P\). It is estimated for the different lengths \(l\) and used to fit the exponential decay function.

This protocol permits the extraction of the decay parameter \(\alpha_\mathrm{crb}\) used to estimate the Error per Clifford \(\epsilon_\mathrm{crb}\).

Assumptions

- This protocol assumes that the noise model is Markovian, meaning that the noise of a gate does not depend on the sequence of previous gates (history-independent). The reader may refer to [5] for an insightful study on the effect of non-Markovian noise on this protocol.

- The average error of all gates is depolarizing (assumption used for all Clifford-based benchmarks).

- The sampled average fidelity of the random sequences must quickly converge to the average for all possible sequences, as only a small fraction of all possible sequences is being implemented. Interesting discussions on finite-sampling effects are given in [5].

Limitations

- One limitation identified by the community [6] concerns the depth scaling associated with the decomposition of each gate of the Clifford group \(C_n\) into single and two qubit gate. This depth scales as \(O \left(n^2/ \log(n) \right)\). As the number of qubits increases, the implementation becomes increasingly challenging, and circuit fidelity tends to degrade rapidly in the presence of noise. As \(n\) grows, the fidelity estimation becomes difficult in practice.

- The output fidelity of the quantum circuit also strongly depends on the compilation process used to map each Clifford gate to the gate set natively used by the quantum computer (single and tow-qubit errors may systematically add or cancel within a single layer of \(C_{n}\)). Inefficiencies or suboptimal strategies in this step can significantly impact the benchmarking results.

- This protocol measures the error rate for the implementation of the group \(C_n\). Hence, the estimation of individual single and two-qubit gates requires an extrapolation, which is not always rigorously valid [7] [8].

Implementation

An implementation of the SRB from IQM is available in their Benchmark suite.

A tutorial for \(C_2\) is available in the QCMet software repository.

References

- [1]E. Magesan, J. M. Gambetta, and J. Emerson, “Scalable and robust randomized benchmarking of quantum processes,” Physical review letters, vol. 106, no. 18, p. 180504, 2011.

- [2]R. Koenig and J. A. Smolin, “How to efficiently select an arbitrary Clifford group element,” Journal of Mathematical Physics, vol. 55, no. 12, Dec. 2014, doi: 10.1063/1.4903507. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1063/1.4903507

- [3]S. Aaronson and D. Gottesman, “Improved simulation of stabilizer circuits,” Physical Review A—Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics, vol. 70, no. 5, p. 052328, 2004.

- [4]D. Gottesman, Stabilizer codes and quantum error correction. California Institute of Technology, 1997.

- [5]J. M. Epstein, A. W. Cross, E. Magesan, and J. M. Gambetta, “Investigating the limits of randomized benchmarking protocols,” Physical Review A, vol. 89, no. 6, p. 062321, 2014.

- [6]D. Lall et al., “A review and collection of metrics and benchmarks for quantum computers: definitions, methodologies and software,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.06717, 2025.

- [7]T. Proctor, K. Rudinger, K. Young, M. Sarovar, and R. Blume-Kohout, “What randomized benchmarking actually measures,” Physical review letters, vol. 119, no. 13, p. 130502, 2017.

- [8]A. Carignan-Dugas, K. Boone, J. J. Wallman, and J. Emerson, “From randomized benchmarking experiments to gate-set circuit fidelity: how to interpret randomized benchmarking decay parameters,” New Journal of Physics, vol. 20, no. 9, p. 092001, 2018.